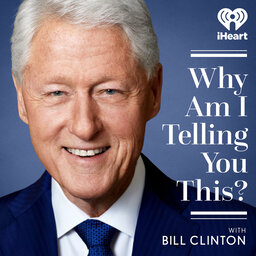

Why Am I Telling You This? with Bill Clinton

President Bill Clinton has always been known for his ability to explain complex issues in a way that makes sense, and for finding a way to connect wit… Roman Mars: How Great Design Can Be 99% Invisible47:41

Roman Mars: How Great Design Can Be 99% Invisible47:41 Secretary Donna E. Shalala, Dr. Harold Varmus, Dr. Francis Collins, Dr. Anthony S. Fauci & More: How to Invest in a Healthier Future1:16:03

Secretary Donna E. Shalala, Dr. Harold Varmus, Dr. Francis Collins, Dr. Anthony S. Fauci & More: How to Invest in a Healthier Future1:16:03 Matt Damon & Gary White: How to Measure the Worth of Water35:30

Matt Damon & Gary White: How to Measure the Worth of Water35:30 David Ortiz: How to Swing for the Fences42:41

David Ortiz: How to Swing for the Fences42:41 Bernard-Henri Lévy: How to Find the Will to See42:14

Bernard-Henri Lévy: How to Find the Will to See42:14 Remembering Dr. Paul Farmer: How to Fight for Health Equity29:38

Remembering Dr. Paul Farmer: How to Fight for Health Equity29:38 Michael Murphy: How Architecture Can Save Lives44:23

Michael Murphy: How Architecture Can Save Lives44:23 Apolo Ohno & Lisa Leslie: How to Be An Olympian56:09

Apolo Ohno & Lisa Leslie: How to Be An Olympian56:09 Jason Isbell: How to Find Something to Love39:57

Jason Isbell: How to Find Something to Love39:57 Introducing: Season 2 of Why Am I Telling You This? with Bill Clinton02:18

Introducing: Season 2 of Why Am I Telling You This? with Bill Clinton02:18 Introducing: You and Me Both with Hillary Clinton01:49

Introducing: You and Me Both with Hillary Clinton01:49 Jimmy Smits: How To Hit New Heights37:48

Jimmy Smits: How To Hit New Heights37:48 José Andrés: How to Feed the World in Times of Crisis32:06

José Andrés: How to Feed the World in Times of Crisis32:06

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, so many of us found ourselves looking at the places we visit in our daily lives, weighing factors like ventilation and ability to social distance, and asking ourselves a new question: will going here make me more or less likely to become sick?

For architect Michael Murphy, this is the kind of question he has spent his life thinking about. As the Founding Principal and Executive Director of MASS Design Group, one of the most innovative architecture and design collectives working today, Michael is devoted to designing better buildings that improve health, bring people together, and promote equality and dignity. In this episode, Michael joins President Clinton to talk about projects they’ve worked on together in Haiti and Rwanda, his new book “The Architecture of Health” and the simple design elements that can limit the spread of disease, and his involvement with the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama. They also share personal reflections on the impact that their mutual friend and partner Dr. Paul Farmer, who passed away unexpectedly the day before this conversation, had on their lives.

Learn more about your ad-choices at https://www.iheartpodcastnetwork.com

Throughout the COVID nineteen pandemic, so many of us found ourselves looking at the places we visit in our daily lives and asking ourselves a new question, well, going there make me more or less likely to become sick. From elevators and office buildings to supermarkets and restaurants, people began weighing decisions around factors like ventilation and the ability to social distance. For most of us, it was a completely new way of looking at our world. Now why am I telling you this, because now, more than ever, it's clear that the buildings we use every day are about more than style and structure. Their design affects our health, how we interact with one another, and ultimately what we value as a society today. I'm so grateful to be joined by someone who spent his life thinking about these questions and trying to answer them in a way that promotes healing, equality and dignity. Michael Murphy is the founding principle and executive director of Mass Design Group, one of the most innovative architecture and design collectives working today. From hospitals and schools and some of the most remote places on Earth, to the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama. His work has changed the way the world looks at design. I've had the chance to work with them many times through the Clinton Global Initiative and to see some of his projects firsthand, including Central Africa's first comprehensive cancer hospital, the Buitaro Center for Excellence in Rural Rwanda. Michael's new book, The Architecture of Health examines the history of hospitals and the simple ways they can be built better today to control disease and promote healing. So, Michael, thanks so much for joining me. Thank you, Mr President, It's an honor to be here with you. Let's start at the beginning. How did you realize that this design work was your calling, both in becoming an architect and also the specific kind of work that Mass Design Group does. You know, the beginning is as a powerful moment for me and as meaningful today. You know, the beginning of the work really started with my introduction to Dr Paul Farmer, who we lost yester yesterday, and um, I was, excuse me, it's hard loss for us. All. I was a young student of architecture and I think, you know, like many students, was wondering, how are work had meaning and what his purpose was, and was learning all around about the work around the world and famous architects and influential architects, but questions of architecture's purpose and who had served and who deserved it. We're sort of lingering out there until I met Paul. And I met him at a lecture. He was giving a lecture on World AIDS Day December one, two six actually, and instead of talking about all the incredible work that he and your organization we're doing to provide anti richer virals to communities that never had them, to lower the price of those drugs, to serve so many more communities around the world, and really fight the epidemic, he was talking about systems design and buildings, talking about clinics and hospitals and schools and housing that they were building under a program the Partners in Health Paul's organizations started called the POSER Program Program on Social and Economic Rights. And I tell you it shook my world. I thought, you know, here's a visionary doctor talking about architecture but calling it healthcare. Yeah, you know, and I never heard I never thought of it framed that way or heard it framed so persuasively that way. And then I went up to him afterwards, like so many students did, and waited for him to talk to every single person in the room as he often did, and said, Hey, I'm a student of architecture. Who are the architects you're working with? Who's building these houses these clinics? And he said, funny you should ask you know, none of you, none of the architects I've ever seen how they can help serve us. We end up having to do it ourselves. When what could you do to help bring architects to rural Haiti, to to rural Rerwanda's and serve our organization instead of waiting for us to ask you how you can be of help. It's kind of an amazing call to action, you know. He gave me his email. I sent him an email later that night. You got right back to me, as he often does. And eight months later I was working with his organization in Rwanda, um thinking about what it means to be in service of their organization and what it means to build healthcare that's truly healing and dignifying. First of all, since you mentioned Paul, I think that I should tell our listeners if you don't know who if Paul Farmer is. He died suddenly on the job in Rwanda, near Butaro, where the University of Global Health Equity is and where this wonderful hospital and what was Central Africa's first cancer center was built with the leadership of Michael Murphy and the Mass Design Group. He also was a man with a million followers. Chelsea has been a devotee and acolyte of Paul Farmer since she was in Stanford, and he's become a very very close friend of mine, and just like everybody else who really knew him, we loved him very much. So yesterday is one of the toughest days and that my family has had a long, long time. I decided we should go forward with his program today because Michael feels the same way, and Paul inspired his work, and I know that he if he were a little bird sitting on my shoulder, he'd say, Okay, that's enough of that, Let's go to work. What what are we gonna do? Anyway, that's the backdrop. If you're interested in Paul Farmer, you should look up one of his many great books, or read Tracy Kidder's account of his life. He's the only guy you will ever run across. I think you graduated from Harvard Medical School, but grew up in a bus that was converted for he and his five siblings. Um. This mom of the teacher's dad was a traveling salesman and they were rich in love and books, and he made it into an astonishing life. So let's go back to you. You founded masses on, which stands for a model of Architecture serving Society, because you believe that architecture has a critical role in driving social change. So for people who have never thought of architect this way, give us some examples of how architecture can solve social problems and micro society healthier and safer and bring us closer together. You know, I do think that question of how does architecture serve us and serve our public better? UM is also about reflecting where it hasn't fully lived up to its potential as well. And UM we learned this in Rwanda. We learned most specifically about how buildings are actually are making us healthier or sometimes making us sicker. We learned that on the hilltop and Pataro, where Dr Farmer passed away and where our first project was because at that time, in two thousands, six and seven, as you know with your work, the epidemic um then was multi drug resistant tuberculosis, a disease that was being transmitted primarily in hallways of rural clinics, of patients with some drug resistance, transmitting through coughing in the hallway to other patients, and then patients coming out with this extremely drug resistant strand. And that was a design flaw. That was a hallway which wasn't designed for enough air flow. Here is a place that makes you sicker, but could be designed very quickly to make us healthier, to protect us. That simple lesson that if you turn the hallways on the outside, you designed the building around air flow. You made it a thinner building so that more air movement could go through it. Simple lessons turn out to be very prescient to what we're going through today. You know, all of us are looking around I mean all I say all of us, I mean all eight billion of us around the world are simultaneously going through this I would say, shared spatial awakening, that buildings around us are threatening us and also wondering how they could make us healthier. First of all, to give our listeners a little more context. Lutaro is a beautiful little place high in the mountains of northeast Rwanda near the Ugandan border, and uh because it's very steep, the angles of the building had to reflect that. And what started out is people thinking about a treatment center for primarily t B actually became a focus for how you could design a hospital so that it was a healthy place, not a place that made people more likely to get sick from touberquet losses. Rwanda. It's like one of the most beautiful places in the world is as you know, it's called the Land of a Thousand Hills, is rolling beautiful, lush, farmed hills um all over this very small country, but very populous country. And this district does as you said, Mr President, is on the border of Uganda. But it's also it was one of the least served in terms of medical infrastructure, so it was around four thousand people in this district and no tertiary care medical facilities. So the government, with the support of Partners in Health and and the Clinton Foundation or CHAIM, prioritize this district as as the place to invest in a new hospital. When you drive there, you pass these majestic lakes nestled into these hillsides with these backdrops of the Verunga mountain chain. It is one of the most beautiful things I've certainly ever seen in the world. And at the top of a hill was was a clinic. It was really just an outpatient clinic. And those clinics looked the same all over the countryside. They were the same design, basically an open room with beds along the perimeter, you know, beds looking at other beds, a central hallway down the middle. And even though that room might have been designed to hold let's say twenty six beds or patients in beds, what you saw and you walked into them were two patients to a bed, sometimes a patient under the bed, not twenty six beds, but fifty beds, all filling the entire room and the hallway. You saw an overcrowded environment, which was increasingly dangerous, especially if you have something like an airborne disease like tuberculosis. So there was a design flaw in that, which was how do we keep these rooms from being overfilled? Can we change the orientation of the beds, can we give the patients a different experience, and tried to protect against over crowding or overfilling. So one of the designs of the wards came from some studies that we looked at that showed that patients got healthier if they had a view of the outdoors. It took less pain medication, they recovered more quickly if they just had a view of a window, and kind of incredible study from the early eighties UM and then also research into the work of Florence Nightingale and others who thought about the war design. It's something to make sure that it wasn't overfilled and could be appropriate place for for the medical staff to make sure that they're seeing all the patients at once and can protect them. So we can we change the orientation of the bed around a central wall that was sort of half height. Each of the beds looks out, so instead of a central hallway, there's two halways on the on the edge between the window and the bedfoot, and that allowed us to kind of have a slightly more rigid floor plans. You couldn't fill more beds into the to the ward and try to protect against overcrowding. His subtle adjustments like that help the care program, help the nurses and staff for saying, hey, this is now an overcrowding problem. We need to create a new award or have a temporary ward, or we need to use other spaces and never to over fill it in and you know, and trigger this other injury you infectious disease transmission. Um to at second point, we started to study how disease was transmitted in the airborne route, and we found from the w h O that twelve what's called twelve air changes prour, which means the volume of the air in the room is transferred every hour, and if you do it twelve times, it's enough air movement to basically reduce infectious disease transmission. And you can do that if you have enough open windows, enough air movement, if you have a big enough room that has air moving in the kind of upper story. So we implemented that there on that hilltop, and um I think really learned about how the building is like a living thing. You know, it's not this fixed object, it's this it's a performative living part of the care program, of the healthcare delivery program. And if we treated it like that, if we paid for it that way, if we designed it that way as a system, we might actually have better performing infrastructure serving more people around the world. Your new book, The Architecture of Health talks about all this, and I found it fascinating. It's it's not just a book for other architects and designers. It's a it's a book that we'll tell us how in an increasingly crowded world we can navigate both peril and promise. Tell us a little about how you came to write this book. We were working with doctors, so they were telling us, you know, proved to me, proved to me that these designs are going to improve the health of our patients, show us through evidence. We had to look at a time when buildings were designed around their climate and their microclimate. They were designed specifically around um, the places they were in, the environments they were in, the cities they were in. And that was of course the case of all buildings until the introduction of widespread mechanical ventilation or the control of indoor air environments through a heating, ventilating and cooling systems in the mid century, in the in the nineteen fifties, in sixties. So every building before then has a sort of inherent intelligence. Not every building, but a lot of buildings have an inherent intelligence that they were designed around their climate. You go to New Orleans, you know, you look at the buildings from the nineteenth century or mid nineteent century. They've really tall ceilings and really tall windows, triple pane windows, and they have these big tall ceilings because air is hot and humid, and you've got to get the air into the room. You've got to bring it up into the top of the room, you gotta ventilated with a fan, and you've got to keep people cool. You go to the Northeast in the United States where I'm from, Upstate New York, the buildings have really small ceilings, the old Hugueno stone buildings and outside of New York City up north and Hudson Valley from the seventeenth century, you know, the stone buildings with really small, big chimneys and short ceilings because they had to keep them hot and warm in the cold climate. You know, buildings design can tell you about the climate. That all changes in the mid century when you know, technological advances allow us to be able to control indoor air climates in a much more comprehensive and a much more sophisticated way. But it also has a sort of devil's bargain. And now that we are required to have mechanically ventilated spaces everywhere we go, um, it's increasing carbon offsets into the climate itself. It's uh making us more and more reliant on buildings that are mechanically run, and it loses some of the inherent intelligence of building themselves. So we learned that on that hilltop because we didn't have the money to pay for a big mechanical system, and we had to look backwards and design something that was naturally ventilated. So this book is that journey. It's looking backwards to see where were the design examples that really showed how buildings are directly addressing our health And turns out so many of them are hospitals because that the hospitals are designed with that healthcare outcome in mind. So they give us a kind of roadmap, you know, roadmap for how we might emerge out of this pandemic and think again, Um, we think differently about how we might design the buildings around us to serve us better. Yeah. I think that's so interesting that because of the financial constraints, we might actually wind up designing healthier buildings. One of the lessons Paul always taught us as a resource limitation creates incredible resourcefulness, you know. And in that condition where we didn't have access to massive supply chains, you know, Rwanda is still rebuilding from the genocide. UM, we had to make do with what was available locally, which you know, forced us to think or or search out for examples which um have universal applicability, which is what which drove us to look at people like Florence Night and Gale and her work in the eighteen fifties, Look at Albert Alto in Finland in the thirties, look at the incredible work of hospible designers for less century and what they were trying to solve for. And so this book is that kind of uh, you know, we're using use it as a my own research project, but also a sort of defense in some way of why why architecture matters so much to our own ability to live, you know, a healthy life, keep us protected. So yeah, we're excited about the book. Also, we have a show at the Cooper Hewitt which I'm ball plug now, but the Cookie Hero Design Museum, which is related to the show, which is how design and designers have responded to epidemics historically and to this epidemic that we're in the middle of. Our world is defined by it in many ways. You know, I think you're a fan of incredible book Ghost Maps, which Dave Johnson's book Ghost Map, incredible book, Steve Johnson's book. Yeah, and you know the story of John Snow's map of Soho, his cholera map of Soho in the eighteen fifties. And for the listeners, it's a there's eight fifty John Snows, he's a scientist before really epidemiology emerges. He takes out a map of the Soho district where there was an outbreak cholera. He makes a tick mark at every household where there's a case, and he sees that there's a concentration of cases around this one part of the street. Um, it goes and looks at that part of the street and there's a water pump. It takes up the manhole cover and sees that there's a waste of human you know, like a sewage pipe broken and putting basically sewage into the water source famously or you know, So the story goes, takes off the handle of the water pump and the epidemic subsides, and hence cholera is not, let's say, morally born, but as water born. I think is one of the great statements in the book that the whole way in which we thought about the solution for solving this scourge cholera was transforming cities across the world for and huge pandemics from the beginning part of the nineteenth century into the mid part of the nineteenth century and threw up into the end of the nineteenth century, just completely ravaging cities and countries around the world. And this changed everything, and interestingly enough, an incredible movement of design emerged called the sanitation Era, where people's governments and city plants started to plan their cities around health outcomes, about separating waste and water, about getting air movement into streets and buildings. Central Park and Frederick law Olmstead is a big part of that movement. Many of our cities in America are driven by those ideals, and they really in a lot of ways, began with John Snow's map, which was this perfect intersection of epidemiology, visualization, visualization tools, and design all together. To a large degree, tuberculosis and cholera were solved diseases. At the end of the nineteenth century, you know, we had figured out a way to design our buildings, design our cities to address it. And that's not doesn't mean that it was gone. It was still endemic in certain areas, but we knew how to solve for it and could implement it with enough resources. But that starts to change, and increasingly more and more places start to see cholera. More and more cities are emerging in unique ways, like you're mentioning, Mr President, which the cities were designed for quarter Prints, I think it is designed for about four dred thousand people and has you know, three or four million in it, So the density, um, it's just completely overwhelming. The systems that they have to separate waste and water very specifically, and old Port of Prints does have a wastewater treatment system, has piped waste in water underneath certain streets in the kind of gritted historic city. But it's the new parts of the city, the neighborhoods that have emerged on very very steep inclines of hills, or this neighborhood called City of God, which was built on the runoff of the big the big drains that were coming down from the mountains and bringing kind of runoff like loose ground into the water's edge, kind of extend the beach. Seventy people live in this largely informal part of the city which has no piped waste and water infrastructure, so it is a perfect breeding ground for something like cholera to take hold and create the kind of epidemic that we saw. So you know, when the design UH request was put out there, we had to ask ourselves, Okay, how does the building address that systemic problem? And the most simple answer as well, if people with cholera are coming to this place, how do we create a building that separates that waste and doesn't recontaminate the ground soil into the city itself and actually collects it, decontaminates it on site and shows as an example how a building can actually cleanse the water it's collected and cleanse the waste it's collected. One of the things you did was put the water treatment above the ground and then put a grass cover on it. Correct and you actually might have like a stylished part of a new sort of design. Talk about that a little bit, because that was the key to to making the place safe. How did you do that? Yeah, well, I mean I think understanding the problem was the first one. You know, what's not just the issue of contaminated water, but what are the kind of social conditions of the disease. Dr Bill Pop was bringing patients. Here was a concentration of of sick patients, and we knew that we would have a lot of contaminated waste we'd have to deal with so big. The way to deal with that is to actually use one of the lawns or in that case was a parking lot and turn it into a grass field that's lifted up, which has the um. The waste that's collected goes through a series of chambers. Each chamber cleans it a little bit more. Nine chambers and what's called anaerobic biodigester, that's the technical term. And then it uh you know, puts the water that that waste water back into the ground. So distributes back into the ground and if it's decontaminated at the ninth chamber, that water is totally clean and able to be put back into the groundwater. That's the way in which your septic system works, of course in your house, and it's the same the same way, it's just a slightly more comprehensive sifting process. We'll be right back. You worked in Liberia, another country that Child works in on in the aftermath of the Ebola problem and the outbreak there was deadly, especially in Liberia and Guinea, and say ear leone and tell us what you did there and how you dealt with the Ebola health challenge. At each of these epidemic outbreaks, we find ourselves, you know, trying to serve the organizations that are trying to address these things in infrastructure becomes a key piece of it. You know, each one of these diseases introduces another type of infrastructural solution. So, you know, Bola, the issue there was physical transmission touching each other or any kind of contamination through skin to skin contact or tears or bodily fluids, and so beyond all of the kind of socialization trauma of not being able to take care of your loved ones or touch them or see them, and sometimes all of that really really horrific outcomes of the Bola upbreak. It was really a space planning problem as well. How do you create basically cleaned, sanitized zones that were decontaminated where caregivers could make sure that they could what's called don and doff, you know, take off their protective equipment and put it back on, so they could walk through areas that they knew were safe and then serve the patients and other patients weren't infecting the caregivers, you know, and caregivers if caregivers start getting sick, as we learned with the COVID pandemic, and that's sort of the canary in the coal mine where there's a problem that is systemic and we need to address it. And what we're seeing with the Bola was that the medical infrastructure didn't provide enough isolation, separation and decontamination spaces so that patients would be protected and caregivers would be protected. So designing a hospital that has really really carefully um thought about each of these threshold spaces where you walk in, you know, you know the contamination level, you're protecting, you're not contaminating the space that you just left, you're not contaminating the patients that are in the spaces where they think they're safe. That's a really really important kind of space planning strategy and something we implemented on a new hospital design for the country. You know, the other lesson I think we learned from that is um after these outbreaks, after these emergencies, there's a ton of out porring of resources and money and and care and interest. And that was the case. You know, billions of dollars were committed to Liberia to sire leone UM, a lot of energy, a lot of emergency response, but there isn't always the investment. There's investment in emergency response, but not always in the long term infrastructure that is going to be necessary to stem the next outbreak or the next crisis. And then I thought it was really telling that the Ministry of Health and Liberia said, you know, we want the money for these this outbreak, but we also want money for investing in our health care system to strengthen that system so that we're protected and prepared for the next one. And they had been thinking about that for a long time. The President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, who so visionary, UM you had said early on before the outbreak, the health system needs to improve in strength in order to protect the country. So UM, I thought they were really ahead of the game. Actually to push back against let's say the aid UM let's say the development industry, which would only pay for let's say emergency of bowla treatment units that would last for a year, and say that's fine, we need those, but we also need the money for a permanent medical facility UM and that was a really powerful outcome, and we've been working on the design of their new central hospital in downtown on Rovia that will bring in all of these lessons from air flow that we learned in Rwanda, waste management we learned in Haiti, and then UM separation of patients in UM, the treatment of ebola, so that all of those are inter twined in the design of this new tertiary care facility that's under construction. I was really thrilled when you started doing that, because when the ebola outbreak happened in Libraria, the government asked try our health group to help them deal with it and stay around if we could, and four of our people actually never left the country and they were miraculously none of them got sick, but a lot of people did. UM. Tell us what you think the implications of what the first line workers front line workers have been through with COVID and what we've learned from that, and is there a way we could design better to deal with such things in the future. Yeah, you know, I thanks for asking that, because I think these lessons in many ways. We were preparing for this moment for last decade, all of us together, working in these epidemic moments and trying to figure out what the spaces could do to help address the diseases were facing. You know, when COVID broke in February, UM, you know, all of us obviously we're thinking about what to do. UM, But it was in April where March and April we started getting calls from our partners, UM, folks that we had worked with in the healthcare industry, saying, how can we immediately you know, support our our constituents, are our clients that people were serving and UM one of them was this amazing group called Boston Healthcare for the Homeless, their network of UM health care services for homeless populations and serving really incredibly marginalized groups suffering in a huge way, and they were getting COVID really in a big way. First, you know, another kind of canary in the coal mine example. And we got a call from an old friend named John Bukavalis, who was at the Cincinnati Children's Hospital. UM, and when I had a research amazing guy, and he had moved recently to Mount Sina Hospital in New York and was leading a lot of their research there. And that was, as some of you somebody might know or may not know, really kind of the epicenter of the outbreak in New York during April, which is really spiking a and um. You know, John reached out and said, look, you know, caregivers are getting sick. We're you know, we're getting sick. We don't know where diseases coming from. We don't know fully all about it. We're just we're in the middle of it. Is there anything we can think about spatially, um, that could protect us, to help us. And so we did this very rapid design research project. We attached go pro cameras to these doctors heads and we did some you zoom based recordings, and we mapped with them how the hallways again of the hospitals we're changing, they were getting filled with equipment. Um. Everyone didn't you know, donning and doaughing was happening in different places. And then we did these exercises too with doctors to figure out where they perceived the risk of the disease and where they were safe and where they weren't safe. And I mean I'm talking, we just took plan It's like the fire escape maps from the walls, and we had them with crayons draw on those maps, you know, green, yellow, and red. And it was shocking and also I mean not fully surprising, but each map was different. Everyone had a different perception of where there was safe space and where there was contaminated space. And it's really illustrative just to see it together because you knew that, oh well, you can work from this. We can visualize like John Snow visualized the cholera epidemic. You can use this visual tool to start to create rules inside the hospital that maybe incrementally would help the caregivers in the middle of the outbreak, just to kind of create clearer lines of delineation between protection and risk. It's amazing, and they were just you know, I just say that it's the doctors and the caregivers that were designing the spaces, redesigning in real time. I think we have the most to learn from about how they're operating within those terrible conditions, and they deserve really all that credit. More After this, you also were involved in the design of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice. Many people believe it's the most important structure that's been built in the last several years in America. And so tell us a little about that. Tell us what it is and how you got involved in it. Well. The National Morpha Peace and Justice is a memorial in Montgomery, Alabama that was conceived, of, imagined, and designed by Brian Stevenson of the incredible Equal Justice Initiative. Just Mercy just a profoundly visionary and impactful organ zation and seat of thinkers that are I think fundamentally changing the narrative around our country's history of racial oppression and terror. I had been a fan, like many people, and I saw an article in The New York Times where he mentioned that their legal work. Keep in mind, Brian, Brian and his team are lawyers. They're fighting for people who are incarcerated, often unjustly, and trying to get them the services they deserve. And he said, we can't do this work without addressing the history of racial terror in America and starting to change the narrative around our history of racism in America. And he said, I want to mark every site of lynching, the lynching of African Americans in America, and I want to build a national memorial to those victims to rise from the ground this hidden history of our country, bring visibility to it, say their names, and recognize that the landscape of of how our public spaces around the country are marked and named and who is recognized UM is not a full and comprehensive list of those who have suffered and died for our freedom. And this is a necessary piece of infrastructure to help heal our nation. So the project is a memorial to the victims of lynching from really the dates are between eighteen eight and nineteen fifty to a large degree, and it's organized by UM the counties across the country and the names of those individuals in those counties who were often publicly terrorized and killed in in particular the post reconstruction kind of Jim Crow era before the advent of civil rights movement. I think the memorials that really succeed are the ones that UM what I would call, transmit the intimate and the infinite. They show the totality of the loss, the totality of the of the crisis. In volume, you know, you can see it it's not just a number on a page or in the newspaper, which is to some degree hard to understand what that is. Four million, six million, ten million, that's hard to understand. But if you see, you know, six million stones in a pile, for example, to commemorate the Jews that were murdered during the Holocaust, that's a huge enormous thing that you can spatially experience. When you see the names on the Vietnam Veterans memorial and you walk and you see the list of names as a volume, it's hard to ignore. Um. It shows that sense of the infinite. But then you have to move past that and create a link to find that individual name in the Vietna Veterans memorials very influential to us because that idea of people coming and finding the name of their loved one, their brother or their father, and rubbing a piece of paper with a pencil and taking away that name on a on a piece of paper and framing that that kind of memento. That experience, I think is really powerful one. You know, it's one where you're like transcending just the legibility of the wall and you're touching it, you're building it. Into your deep memory that experience. It's unforgettable, and then you feel it. You feel the weight of all of those markers above you as um um, the kind of weight of history that we haven't fully uncovered. You know that we don't fully know that weight of history. You feel it in your body, and that to me is where architecture is doing necessary things. You know, Um, this is a very pull Farmer way of thinking about it. But is the question of what can we not accomplish without spatializing it? Yeah, memorialization is necessary because we need to create a space or a location where we can go and wrestle with pay tribute, understand, but also um, create a unique memory in our own selves that we witnessed this history. So where where are you going from here? With all this? I returned often to this amazing quote from you know Dr King and his letter from Birmingham Jail, where he talks about the garment of destiny. Whatever affects one affects all, that we're all tied in an inescapable network of mutuality. I love that line. I think buildings are the places where we experience that mutuality, that garment that connects us all is found and forged in the public realm and the public places that we have to go and choose to go. And if it's the post office or the hospital waiting room, or if it's the school where we attend, those places transform us. And I think periods before I think of the w p A, I think about the New Deal, I think about these moments where we understood that as a country, where we invested not just in the infrastructure that was necessary to survive, but that we invested a sense of dignity and artistry and commitment to the beauty of it as essential as elemental. And we've done it before. I think we can do it again. I think we could really take that mantle. We ourselves can enact change through our buildings and through the world around us. I think those are the lessons I hope to carry forward. Thank you, Michael Murphy, your inspiration and mentor. Paul Farmer was very proud of you, and I'm very grateful to you, and I can't wait to see what you do next. And I urge all of you who are interested in these things to look up mass design on the internet and read about them, and look at the architecture of health. This is very important stuff. But as I hope Michael has persuaded you, it's also a challenge to the modern world that is accessible to us, one that we can make a den end, often without spending enormous amounts of money, are bringing in from somewhere else, staggering amounts of expertise. It's what they have accomplished that mass design is largely a feat of the imagination, possibility of wonder being made out of things that are at hand and people that are handy. We're all in your debt, and I wish you will thank you. I thank you so much for this conversation, and thank you for um the opportunity to speak with you today. In the passing of our friend Michael, and I will began to sound silly if we don't stop this. But once you to watch in a lifetime you might meet somebody like Paul Farmer, somebody so extraordinary and yet so real, so commanding and yet so human and hilarious, uh that it changes your life forever. And we're dealing with that loss now. A man who was sixty two and should have lived twenty years longer or thirty years longer, but who did outlive his own father about thirteen years in a family prone to heart disease. She was a social hero, if you will, but he was a wonderful personal friend. Thank you, Michael, Thank you, Mr President. Why am I telling you? This is a production of My Heart Radio the Clinton Foundation and at Will Medium. Our executive producers are Craigmanascian and Will Malnadi. Our production team includes Jamison Katsufas, Tom Galton, Sarah Horowitz, and Jake Young, with production support from Liz Rafferee and Josh Farnham. Original music by What White. Special thanks to John Sykes, John Davidson on hell Orina, Corey Ganstley, Kevin thurm Oscar Flores, and all our dedicated staff and partners at the Clinton Foundation. Hi, I'm back a Courtsield and I'm a Deputy director at the Clinton Global Initiative. President Clinton established the Clinton Global Initiative to create a new kind of philanthropic community. To address the complex realities of our modern world. We're problem solving required the active partnership of government, business and civil society. Over the years, are Proven model has grown to include action networks that can quickly mobilize in the face of emergencies, whether that's helping Puerto Rico and the Caribbean recover in the wake of Hurricanes Rman and Maria, or advancing an inclusive US Economic recovery amid COVID nineteen. To learn more about this work and see how you can get involved, visit Clinton Foundation dot org. Slash Podcast

Why Am I Telling You This? with Bill Clinton

Why Am I Telling You This? with Bill Clinton