Why Are Airline Rewards So Complicated?

Frequent flyer programs began as a way for airlines to build loyalty and fill empty seats. They’ve since morphed into a complex financial ecosystem that’s drawn the ire of even the most savvy consumers and the scrutiny of the US Department of Transportation.

Bloomberg’s global aviation editor Benedikt Kammel joins David Gura to talk about points, miles, qualifying trips — and how we got here in the first place.

Read more: The Airline Rewards Game Is Getting Tougher to Win

In 1 playlist(s)

Big Take

The Big Take from Bloomberg News brings you inside what’s shaping the world's economies with the sma…Social links

Follow podcast

Recent clips

Special Report: US and Israel Strike Iran

11:55

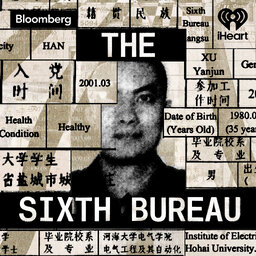

The Sixth Bureau Episode 4: The Duck Analogy

33:40

How the ‘Power Game’ Is Reshaping Venezuela

18:05

Big Take

Big Take