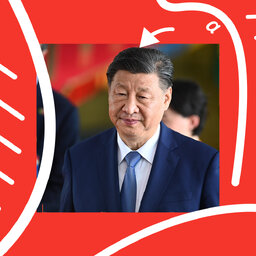

A network of dictators from China to Venezuela could be the beneficiaries of a welcoming White House should Donald Trump win the US election come November. That’s according to journalist and historian Anne Applebaum, who warns that the self-proclaimed dealmaker and convicted felon’s foreign policy may be more personal and even less predictable in a second term. Applebaum joins Voternomics host Stephanie Flanders to discuss her latest book Autocracy, Inc: The Dictators Who Want to Run The World.

In 1 playlist(s)

Trumponomics

Tariffs, crypto, deregulation, tax cuts, protectionism, are just some of the things back on the tabl…Social links

Follow podcast

Recent clips

What Munich Means for the Shifting Global Order

28:47

Understanding Kevin Warsh's Plan for the Fed

31:28

How Trump’s Year of Disruption Has Only Helped China

27:24

Trumponomics

Trumponomics