Mark Manson, author of 'The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F**k' on how the self-help industry gets it wrong

In today’s episode, American author, speaker and blogger Mark Manson discusses how the mantra of relentless positivity, which drives so much of the self-help industry, is full of pitfalls. He explains how negative emotions have a purpose - to drive us to do something - and why the willingness to look like an idiot occasionally guards against self-entitlement. He gives us tips on how to be realistic in our lives, how to maintain hope - and what not to do with cyber stalkers.

Hosting this talk is Good Weekend deputy editor, Greg Callaghan.

In 2 playlist(s)

Good Weekend Talks

Good Weekend Talks features in-depth conversations with the people fascinating Australians right now…Social links

Follow podcast

Recent clips

Why we run: Konrad Marshall on 365 days of jogging

31:34

Brooke Blurton is successful, smart and Indigenous. And still, trolls tell her she's 'on Centrelink'.

36:09

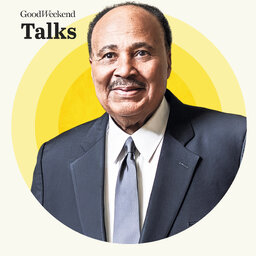

Martin Luther King III on retaining hope in today’s world: ‘Civility has been temporarily lost’

36:49

Good Weekend Talks

Good Weekend Talks