Secretary Donna E. Shalala, Dr. Harold Varmus, Dr. Francis Collins, Dr. Anthony S. Fauci & More: How to Invest in a Healthier Future

In existence for over a century, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) is arguably one of the most important agencies of the federal government. Its work is so critical that it often enjoys rare and widespread bipartisan support. In this special bonus episode, President Clinton and nationally recognized experts share first-person accounts and unique perspectives of how the Clinton administration’s unprecedented investment in research and science at NIH led to some of the most impactful scientific breakthroughs in the last century – including developing antiretroviral treatments for HIV/AIDS, accelerating research which ultimately made it possible to develop COVID-19 vaccines, and the sequencing of the human genome.

This episode features talks by:

- President Bill Clinton, 42nd President of the United States, Founder and Board Chair, Clinton Foundation

- Dr. Donna E. Shalala, Secretary of Health and Human Services in the Clinton Administration

- Dr. Anthony S. Fauci, Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the NIH

- Dr. John I. Gallin, NIH Associate Director for Clinical Research who served as the inaugural chief scientific officer of the NIH Clinical Center

- Dr. Gary Nabel, President & CEO of ModeX Therapeutics and the first director of the NIH Dale and Betty Bumpers Vaccine Research Center

- Dr. Harold Varmus, the Lewis Thomas University Professor of Medicine at Meyer Cancer Center of Weill Cornell Medicine, former Director of NIH, and Nobel Prize winning scientist

- Dr. Wendy Chung, Director of Clinical Genetics at Columbia University

- Dr. Francis Collins, longstanding former NIH Director and Director of the National Human Genome Research Institute

- Dr. Charles Rotimi, Director of the Trans-NIH Center for Research on Genomics and Global Health

This podcast was adapted from an event held in partnership with the Clinton Presidential Center and the University of Arkansas Clinton School of Public Service as part of the Kumpuris Distinguished Lecture Series. To learn more, visit www.clintonpresidentialcenter.org.

In 1 playlist(s)

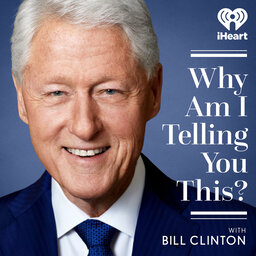

Why Am I Telling You This? with Bill Clinton

President Bill Clinton has always been known for his ability to explain complex issues in a way that…Social links

Follow podcast

Recent clips

Prime Minister Tony Blair: How to Define Our Interdependence

47:36

President Bill Clinton: Reinstate the Assault Weapons Ban Now

08:00

Dr. Jill Biden and Hillary Clinton: How Community Colleges Can Build A Modern Workforce

26:00

Why Am I Telling You This? with Bill Clinton

Why Am I Telling You This? with Bill Clinton