Low Pay, Long Hours, Rude Customers. Retail Workers Have Had It

Retail work has always been hard – long hours and weekend shifts on your feet, a lower pay scale and dealing with disgruntled customers. But in our post-pandemic economy, those issues have only been amplified with shoppers behaving badly and wages not keeping up with inflation, while employees take on ever-expanding roles. As a result, many workers are deciding the job just isn’t worth it.

Bloomberg’s Devin Leonard and Rebecca Greenfield explain the decline of retail workers’ sense of value and respect that is leading them to quit in droves. And retail reporter Olivia Rockeman talks about the broader challenges facing brick and mortar stores as they try to compete with growing online sales.

Read more: US Retail Workers Are Fed Up and Quitting at Record Rates

Listen to The Big Take podcast every weekday and subscribe to our daily newsletter: https://bloom.bg/3F3EJAK

Have questions or comments for Wes and the team? Reach us at bigtake@bloomberg.net.

In 1 playlist(s)

Big Take

The Big Take from Bloomberg News brings you inside what’s shaping the world's economies with the sma…Social links

Follow podcast

Recent clips

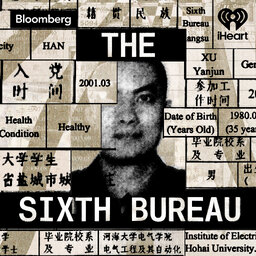

The Sixth Bureau, Episode 2: The Spy’s Diary

30:28

The Sixth Bureau, Episode 1: Your Friend From Nanjing

12:43

Trump Accounts Promise Free Money. What's the Catch?

18:56

Big Take

Big Take