Insurers Are Struggling to Keep Up With Disasters Like Helene and Milton

In recent weeks, two monster storms have pummeled the US. Hurricanes Helene and Milton left more than 200 dead — and early estimates suggest the recovery could cost more than $100 billion. It’s a huge strain on affected homeowners and the insurance industry that’s meant to shoulder some of that burden.

On today’s Big Take podcast, Bloomberg’s Leslie Kaufman joins host David Gura to talk about the increasing severity and frequency of extreme weather events, and how the new normal is changing the calculus for insurers.

Read more: Federal Flood Maps Are No Match for Florida’s Double Hurricane

In 1 playlist(s)

Big Take

The Big Take from Bloomberg News brings you inside what’s shaping the world's economies with the sma…Social links

Follow podcast

Recent clips

Special Report: US and Israel Strike Iran

11:55

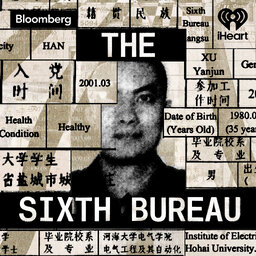

The Sixth Bureau Episode 4: The Duck Analogy

33:40

How the ‘Power Game’ Is Reshaping Venezuela

18:05

Big Take

Big Take