A Uranium Mine, the Navajo Nation and a Six-Month Standoff

On Wednesday, the Navajo Nation and the mining company, Energy Fuels Inc., announced a new agreement detailing how uranium could be transported through tribal lands.

The agreement ends a stalemate between the two parties. And it comes at a time when interest in nuclear energy — and the cost of the uranium that fuels it — is surging.

On today’s Big Take podcast, Bloomberg’s Jacob Lorinc joins host Sarah Holder to break down the painful history of uranium mining in the Navajo Nation and what the dispute reveals about the human costs of “clean power.”

Read more: Uranium Fever Collides With Industry's Dark Past in Navajo Country

In 1 playlist(s)

Big Take

The Big Take from Bloomberg News brings you inside what’s shaping the world's economies with the sma…Social links

Follow podcast

Recent clips

Special Report: US and Israel Strike Iran

11:55

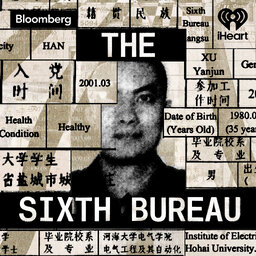

The Sixth Bureau Episode 4: The Duck Analogy

33:40

How the ‘Power Game’ Is Reshaping Venezuela

18:05

Big Take

Big Take