Monster

Atlanta, Georgia 1978, children are going missing one-by-one, their bodies discarded in nearby lakes. Vallejo, California, 1968 a crazed killer in an … BTK | Bonus | Susan Visits the Sites25:12

BTK | Bonus | Susan Visits the Sites25:12 BTK | Bonus | 50 Years of BTK with Larry Hatteberg35:45

BTK | Bonus | 50 Years of BTK with Larry Hatteberg35:45 BTK | 10 | El Dorado46:35

BTK | 10 | El Dorado46:35 BTK | 9 | The Trial39:44

BTK | 9 | The Trial39:44 BTK | 8 | Dennis Rader46:34

BTK | 8 | Dennis Rader46:34 BTK | 7 | BTK Returns40:15

BTK | 7 | BTK Returns40:15 BTK | 6 | PJ Green38:04

BTK | 6 | PJ Green38:04 BTK | 5 | Boy Scout46:11

BTK | 5 | Boy Scout46:11 BTK | 4 | Shirley Locks49:28

BTK | 4 | Shirley Locks49:28 BTK | 3 | Bright43:42

BTK | 3 | Bright43:42 BTK | 2 | Childhood of a Killer43:14

BTK | 2 | Childhood of a Killer43:14 BTK | 1 | The Otero Family41:13

BTK | 1 | The Otero Family41:13

Why was the Phantom never caught? Is it possible he's still alive, walking freely? We explore all evidence pointing to his identity. And we ask: what hope is left?

You're listening to the Freeway Phanom, a production of iHeartRadio, Tenderfoot TV, and Black bar Mitzvah. The views and opinions expressed in this podcast are solely those of the podcast author or individuals participating in the podcast, and do not represent those of iHeartMedia, Tenderfoot TV, Black bar Mitzvah, or their employees. This podcast also contains subject matter that may not be suitable for everyone. Listener discretion is advised.

Freeways are interesting because millions of people use them, but very few people walk along the sides of them. They're very accessible, but they're also not generally used for foot traffic, and so it's very easy to conceal someone just off of a very very busy highway because nobody usually walks along there. It means that he one has a car, two knows when he can get on and off that road without being detected. Most likely has a job or family situation which allows him to be out at any hour.

Of the day or night.

Because, believe me, choosing these victims and abducting these victims took a long time. He had to be out there a long time to get access.

To these particular victims.

They weren't doing things that they did every day at that time. That means he has to be available to wait for them to show up and to follow them, and then to be vulnerable. So they're not vulnerable while they're inside a.

Store or with other people. They're vulnerable when they're alone.

This is exactly who he wanted, and he was willing to take a great risk to get her.

The homicide detectives termed the cases the little girl cases.

This child was laying on the side of the road. I wouldn't go no way.

I would call up my house.

Those first five murders should have been a huge warning bell for the police.

We just want to know what happened. This person must have saw that They was thinking that maybe it's just one person, and he says, uh, they need to know. This is me.

I thought that they would catch him. I thought it was just a matter of time.

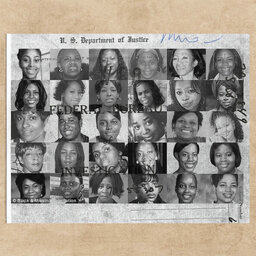

I'm Celeste Headley and this is Freeway Phantom. In the previous seven episodes, we covered the murders of eight young black girls, ranging in age from ten to eighteen years old, that occurred in DC from nineteen seventy one to nineteen seventy two. There were six confirmed victims of the Freeway Phantom. And then there was the case of Angela Barnes, originally co ittered victim number three, whose case was closed after two police officers were convicted of the crime. Then there was Tera Bryant, originally considered the final victim, who was eventually removed from the Freeway Phantom victim list. And two things are unclear about TERA's case. Who removed her from the investigation and why. Fifty years later, Detective Romaine Jenkins still believes that Tara was yet another victim of the Freeway Phantom, although her family believes otherwise. As we learned in the last episode, law enforcement turned their attention to the Green Vega Gang in nineteen seventy four, and although they were officially ruled out as suspects in the Freeway Phantom murders, many in law enforcement assumed they were responsible. Others thought Robert Askins was the likely killer, a suspect we talked about in episode six. All of this led the majority of the Metropolitan Police Department to conclude that the cases were solved, but not Detective Romayn Jenkins.

Were looking for the wrong person. They didn't know about profiling, and all of that They're not looking for the guy who hides behind a tree, you know, this dastardly guy who's gonna grab a woman, some psycho. That's not what they were looking for, and that's what they went after.

For ten years, the case files sat there called untouched, until Romayne took over the case in nineteen eighty four.

So I had at my disposal, I had seven senior homicide detectives, and I decided, I said, why not use them? And some of them had actually worked on the cases traitionally, yeah, originally, And they gave me their notebooks and so forth, and they, you know, could you read all their handwriting? Uh huh. See, back then, we were the carbon paper typewriter folks. There were no computers. We didn't have computers. You had to type everything and man ooh, you had to be detailed. And we work closely with the medical exams this office, so you know, we learned a lot about anatomy and causes of death and things like that. We investigated causes of death.

Although she was now leading a team, many in the police department weren't too happy about having a black female supervisor. Romayne says that throughout the nineteen seventies and eighties, racism was alive and well in the MPD racism.

You talk about racism, Oh yes, I just signed black officers to a scout car and I'm riding along in the area and I see the black officer walking the footb. Is what you're doing walking up footb? The lieutenant took me out the car and put officers on. So and those are the things that they did back then, you know. So racism hadn't gone away, you know, sexism and sexism because because the women were mistreated by the officers they were, they tried to intimidate some of them, you know, and some of the women, some of the women just said, you know what, this is not for me, and they left the job. You know, they actually left the job. And as a supervisor on the job, you know, I thought I would have some power, but no, I really didn't. And I know one time my lieutenant asked me, he said, Sergeant Jenkins, do you think I'm a racist? And I said, yes, sir, you are. And he says, I'm not a racist. My next door neighbor is black. I said, Lieutenant, the only reason your next door neighbor is black is because you don't have enough money to move out the neighborhood. See. I was like that because my husband was president of the Afro American Police Association, so there was a militantcy. I had an instance where two of my officers, one white and one black, they saved a little three year old who had been left in the car and the car burst out in flames, and officers went in and got that child. I wrote the officers up to the awards committee, only the white officer's name went. I mean, they would do things like that, and so I was always constantly, you know, in battle with them. And I said, you know what, I'd enjoined the police department to go through us. I mean, these are the things that I had to face out there. The commander at that time, I went to him, I said, sir, we have a problem over here. He said, what's wrong. I said, you know, the policewomen, these black police women are being harassed, They're being mistreated. I said, I think we only had like one or two white females. And the white girl who came from Connecticut who had never seen a black person before. They gave her a short beat around the station. That was her assignment. She had to walk around the station for the tour of duty. I mean, this actually happened. And so I said, you know, we're having a problem and something has to be done. He said, well, you know what, and he was white. He said, we're not going to tolerate. He said, I want you to do an investigation and let the chips fall where they may. And so I said okay. And in the end room, a black officer came there and say, look, Sorge, and be careful because the white officers gonna get you. He said, I don't know what they planning, but they plotting something. He said. I was in the locker room and I got bits and pieces of the conversation. They're gonna do something to you because they upset that you initiated this investigation of the things they did to the black police swiomen. So I said, thank you. And it wasn't no longer than a day or so later. Whenever my troops went on a run, I'm just a supervisor. I'm out there riding up and down in a scoutcar. I go and see how they handle it. I'd go park in the neighborhood and watch how they handle how they interact with people, and I got out the car and I was walking towards them. Well by then they had cleared the runs at ten eight nothing found or whatever it was. And so as I was walking back to my to my scout car, they got in the car and the officer gunn in the car. I had to jump up on a citizen's car to keep from getting hit. I was, Oh, was I hot? I was hot? So I didn't say anything. When I got in my scout car, I went over the air and asked the dispatcher to locate that unit for me and have them meet me at there. Stand by their location. I'm responding. They stood by. I went to their location and I told it was two white officers and I told them, whatever you applied and to get me, make sure that you don't miss the next time, or else I'm going to kick your you know, and I use the word you can use it, yeah ass. And if I can't whip your ass, I have a husband up in three D Whu's six foot two, and he will do it. But don't miss the next time. They didn't say nothing. They went on back and got in the scout car and drove off.

It is so difficult for me to hear you tell these stories about the way the police force was in the nineteen seventies and think that that prejudice, that racism didn't hamper the investigation. That they may have invested a lot of officers hours and energy and focus and time into the investigation. But how were these detectives not let us stray by their own prejudices.

Oh, they had to be. They had to be because first of all, they didn't understand the community that they were investigating. I say, you know, police are representative of the communities that they police. If the citizens act wild and crazy, the police are the same thing. That's that's the same kind of thing you're possibly be going to get. Here is the thing. Sometimes, as a police officer, you have you've got to put aside your personal feelings. The only person who ever tried to kill me on the Metropolitan Police Department was a black police officer. Okay, you know, a black police officer tried to kill me and he ended up getting arrested. So you can't say all the white police officers bad. There's some black ones just the same.

You know.

By the mid eighties, Romaine and her team were entirely focused on the Freeway phantom case, and Romayne had her work cut out for her.

When I first started, one of the first things I did was's tried to find the evidence. When I checked with the Metropolitan Police Department and I found that the evidence had been destroyed. The officer took me to the property book where the evidence was and said evidence has been destroyed. So say, oh, that's a DC for me. So then I contacted PG County. PG County found the evidence in their cases, and I got a technician from the FBI to meet me and another detective over in their property office and we went over the evidence. Conclusion was they hadn't preserved it well enough that they could get any type of DNA, but that was back then. They have made advances now now whatever happened to that evidence, I don't know.

But Romayne was able to start making some connections with the evidence she did have.

That's when I saw the report about the green fibers. That's what really piqued my I said, nobody never mentioned anything about green synthetic fibers. And I asked a couple of the people who I knew who had worked on the investigation, and they said didn't know anything about green fibers.

Well, investigators did initially identify the green fibers on each of the victims. Somehow they failed to connect them or analyze them conclusively. Remain decided it was time to make that happen.

Well, see what happened is no one knew about the green synthetic fibers until Detective Lloyd Davis developed Askings as a suspect. When Davis had requested that all the evidence be sent to the FBI, that's when they came back about the green synthetic fibers, which aren't really green if you see them visuals. Now, this is what the FBI technician told me, the guy who handled the cases to the naked eye, they are different color. They're only green if you look at them under a microscopt What are the sources of the fibers? That's that's what I wanted to know about the fiber evidence. And he did the fiber evidence in the Wayne Williams Atlanta murders. So I figured he's gonna have some credibility which was also green.

Actually, yeah, coincidentally.

So I asked him, I said, well, you know, what's the source of the fibers? He said he thought they came from an auto. But I talked to Detective Lloyd Davis, who had all the evidence submitted. He said he was told that the fibers came from a bathroom. Mate like a bath mat and a bathroom, and that goes along with these victims being washed and cleaned. I said, that sounds about right as far as I'm concerned.

One of the most important things that remain did was submit evidence to the FBI to get the first official profile of the killer, and they came up with some intriguing conclusions.

They felt that this person was in the military. Well, at that time, you had all these military people coming back from Vietnam who were in hospitals here and installations here, so you had a lot of that going on. But that was really interesting. And the reason why I thought it was so interesting was because when I showed the note to the FBI, they said, this is military. This person was in the military. I showed the same note to the investigator at Naval Investigated Service. He said, oh, whoever wrote this note? This military? So I had two different brains saying the same thing. You know that this person was in the military.

Romaine eventually retired from the police force, and with her retirement, the case essentially went cold. That was until it was picked up in the early two thousands by former DC homicide detective Jim Trainam, who stumbled into it almost by accident.

That kind of took over a project where we were looking at all of these unsolved cases involving women in DC, like one hundred had been identified over a ten year period by the Washington Post. And that was also during the time period where they first started the coda's database. You know, before you really couldn't do anything with DNA unless you had a named suspect to do a one to one comparison to. But with codas, she could put the information into a database, it would run it against other cases, it would run it against a database or a collection of suspects. So it was during that time when I was first getting started somebody came to me and asking me about the Freeway phantom case, and I really didn't know anything about it at the time. I began to do research and poll what I could, and basically I found the very minimal paperwork, just entries in our homicide log book, and that was pretty much it. We didn't have any files we didn't have any evidence. And the more I looked, the more I realized, like you know, all the cases that were out in PG, they really didn't have any files. They had some evidence that they were looking at in the Wooded case, but everything had pretty much been destroyed, and so I was just trying to build what I could based on these paper accounts and things along that.

Line, much like Romayne decades before him, Jim train And discovered that the evidence in the case had been poorly maintained, either damaged or mysteriously missing. But he slowly started to connect some dots.

So I was able to some stuff from Prince George's county. And then we found out that the FBI had gotten involved in the Worder case and they had quite an extensive file. I was able to get that and make a copy of it as well. I was continuing to look for evidence during that time, kept finding nothing, nothing, nothing. And after we got the FBI file and we learned about people like, let say, Romaine Jenkins who had information as well. I was approached by Dale Wilbur of the Washington Post, and you know, he wanted to do some work on cold cases, and so he was asking me about cases that I thought would be interesting, and I had mentioned the Freeway Phantom to him, and so he thought that was going to be a good case to the feature, And so we pretty much gave him open access to our files that we had at the time because it was so old, we figured it wasn't going to do any harm.

So he did.

What I really wanted to do was that he actually went out and knocked on the doors of the detectives who actually worked on the case originally, and they would invite them in and they would say, yeah, I know all about it. I'll talk to you about it. Come on in, and by the way, would you'd like to see my file. It turns out that a lot of them missing files had been taken home by the original case detectives for later that back in the eighties, they were packing up a lot of those files. Because of the way that files were retained back then, they were throwing out a lot of things like crime scene reports, photographs, witness statements and all of that on all these cases, including the Freeway Phantom case. And that's been changed because of the law, they can't do that anymore.

One of those people was Romaine Jenkins, who kept most of the files from the Freeway Phantom case in boxes in our house. These are the very same boxes that we sifted through when we visited her home.

Well, here's some of that carbon paper you're talking about.

Yeah.

That all I had to do was okay, See the police department likes to throw away stuff. Yeah, and I don't throw away nothing because you never know when you're going to see it again.

Oh, it looks like it's from the memorial service.

That the memorial.

This is Ninemosia's autopsy reports or foot tall and one.

Hundred pounds.

Student at Kelly Miller Junior High School in the sixth grade.

That's tough.

Photos are not here, but.

I think the ends.

The thing.

She realized that a lot of the files were being purged, so she actually took all the purge material and kept it herself. So between her and her institutional knowledge and what Dell was able to gather for us, we were able to recreate a lot of the original files, and so we had a good foundation to work on from there.

Jim Treeham says Roman was instrumental in his reinvestigation of the Freeway Phantom case.

She is wonderful.

I mean, her memory of this case. Anything that I say that is contradicted by her, go with what she says, because where I have, you know, files and reports that I am working off of and all that. She has a great institutional memory about what was actually going on during that time, which is so important because she knows, you know, what, not only what the department was like, but what was those neighborhoods were like, what the relationships were between the department and the neighborhoods and the media and all of that. And just talking with her, I always learned something new. We talked several times, you know, during that time period, and we've actually talked several times since where we've discussed various issues.

On the case and all of that.

And you know, she was able to help us out, you know, quite a lot, because even with what we were able to gather, when you're digging through these old files and stuff, you're almost like an archaeologist. You're trying to kind of piece together little things, and some of the documents that you would come across, they would make reference to things that you would go, well, where is that? Where is that in another document? And you can't find it, So you know that at some point something existed.

After some digging, Jim and his team were able to identify some new evidence that hadn't been thoroughly looked at before.

During the time that we were working on this, we basically learned that there was evidence available from two of the different scenes. One was that PG County had evidence from the Brenda Woodard case. It was part of the sex kit that they submitted to the Maryland State Police lab. And at that time the technology is in advance as it is now, they weren't able to get a DNA profile off of the material that was left, and there was so little material left that they actually used it all up, and so we pretty much hit a data end right there. The second evidence actually came because of our work. We were trying to promote the case and get information out there about it, and I was doing a presentation on it to the mid Atlantic Cold Case Homicide Investigators Association when a cold case investigator from the Maryland State Police said, wait a minute, the last victim, Williams, that's our case. And it turns out we didn't know that, but because of where her body was found, the Maryland State Police had actually become involved in her case. And so they actually had more case files that we weren't aware of at the time, and they had a box of some of her clothing, which was pretty exciting for us. And it turns out that, you know, her underwear was in there, and there was a possibility that there were some seamen stains, and so that was eventually submitted back to the Maryland State Police Lab. But a follow up investigation that was also being done by the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children they were helping out as well. It turns out that that was a boyfriend. She had been with her boyfriend earlier that evening. He had dropped her off with the bus stop, and he definitely had an alibi, so he wasn't involved. And so unfortunately we hit dead ends on both accounts. But at least we now.

Know that we feel pretty comfortable that we've tracked down what is out there. Not to say that something might not pop up in the future sometime, but hopefully it will, but you know, we've pretty much covered those bases, we think.

Trainham says that by far the most success they had was with the profiles. They developed a new geographic profile, which we talked about at length during episode six. They also followed up on the original psychological profiles, including the one commissioned by Romaine Jenkins and completed by the FBI, but he says the track record of profiling throughout this case had been sketchy at best.

At the time that the case was ongoing. At first, what was actually happening. They went to several different psychiatrists psychologists in the area, and they talked to them and got various very different profiles.

I mean, some were.

Talking about how the persons psychotic, we're talking about No, he's more like a normal person. Some talked about how he would be triggered by the name Denise. Others disagreed with that, and so they were all over the charts. The FBI did do a profile several years later, where I think they were much more grounded in the case. Plus they had more experience working with this type of personality or at least reviewing cases that were committed by this type of person, and so they had a more factual background.

Training believes that psychological profiles can be dangerous for investigators.

Profile is only as good as the information. Plus it's not going to point to one person. The profile is going to help you prioritize who you look at over other people. And you know, the profiles that I've worked with in the past, you know basically tell you don't eliminate somebody simply because of the profile, you know, just put them lower on the list to investigate. And I had mentioned it is only as good as the information that they're given. And a lot of times what we do is we would go ask.

For a profile. Here, miss the profile.

Here's our case file, look at it. Tell me what you think. We get the profile back. Six months later, my case follows down this and I lock up somebody or identify somebody as a suspect who doesn't even come close to this, and I'm going out a profile still good. But if I had kept them abreast of all the incoming information at the time, then they could have modified their thoughts and given me better investigative leads as new information became available. So that's how we don't take advantage of this information.

Tretam warns that profiles, especially inaccurate ones, can lead to what he calls tunnel vision.

The tunnel vision is basically focusing in on a suspect or a theory to the exclusion of any other. Now, at some point in an investigation, you have to kind of start doing that, because once you start to identify your suspect, then you begin to build a case against them. It goes from being an evidence based investigation to not a suspect based investigation. The danger is is that you get confirmation biased. The confirmation bias is that you now have tunnel vision, but you're only going to seek information that confirms what you believe to be true and you're going to ignore information that contradicts that. So, you know, tunnel vision is not that bad. You just have to be able to have somebody say, hey, wait a minute, you know, tap you on the shoulder. Did you think about this? Oh no, I didn't.

Let's go look at that. That sort of thing.

So oftentimes somebody may get a profile or may focus in on this is who we think it is because of this, and then they will start trying to make the person fit the evidence, rather than seeing where the evidence takes them to the person. But we also have a tendency to focusing on people who we don't think are acting appropriately. You know, the strange guy and all that. But you know, people act the way they do, and when we project. That's not the way I would act onto somebody. We've gotten off track many times by doing that sort of thing, rather than recognizing that no people can act all sorts of ways and it.

Can be normal.

Triam says this sort of tunnel vision was evident in the Freeway Phantom case. Their original profile of a mentally ill man is what convinced so many people in law enforcement that Robert Askins was the case.

And here, just like with all the profiles that they were getting from all of these psychiatrists and everything, the reason they were going to these people is that they thought this escot was mentally insane. He was, you know, somebody who should stand out in the psychiatric community as having been treated for whatever ailments he had. And that's not necessarily the case.

Train and Stress is that it's crucial profiles be constantly updated with new information. If a profile is years or even months out of date, it can lead investigators in the wrong direction. However, Jim is optimistic that with modern technology and our current understanding of profiling, we can and should continue working on the Freeway Phantom profile.

Things have come a long way since the seventies and eighties, so I would be very interested to hear any updates that anybody might have.

That's exactly why we decided it was time for a new profile, something that hasn't been done since the mid two thousands, and we found the perfect person to do it, the former FBI profiler who cracked the DC Sniper case and blew the lid off the Whitewater investigation.

I'm Jim Clemente.

I'm a retired FBIS Supervisory special Agent and profiler, and I'm also the co founder of XG Productions and so I write and produce and developed content for all platforms.

Our team first discovered Jim Clemente a few years ago during the production of Monster DC Sniper. Jim played an instrumental role in developing the criminal profile in that case. He spent years as a profiler with the FBI, and after leaving, he went on to produce multiple seasons of the show Criminal Minds. We thought there's no one better to make a new profile for the Freeway Phantom, and we started by asking him about the foundations of criminal profiling and how it's come to prove such a success.

So how does one become a profiler?

Well, in the FBI, you have to first become an FBI Special Agent and then go through the FBI Academy and then work about ten years at least on major cases, cooperating with local police departments, state police departments, and other federal agencies and get enough experience on major cases that you have something to bring to the Behavioral Analysis Unit. So the Behavioral Analysis Unit is housed in the National Center for the Analysis of Violent Crimes in Virginia at the FBI Academy, and the Behavioral and EUSIS unit is where the profilers are trained and they work. It basically descended from the FBI's Behavioral Science Unit, and that was started by Howard Teaton in the early seventies, and it evolved from a unit that had a few people to one now that has five or six separate units and twenty five to thirty five active FBI profilers.

You know, the case as you know that we're working on is from the nineteen seventies when we didn't even say serial killer. So I have to imagine that the science of profiling has evolved a lot. You know, at the time, if you read some of the early accounts of trying to figure out what makes a serial killer and you see some of these the early attempts, right, trying to figure out what distinguishes a serial killer from another type of murderer.

That seems to have really evolved over the years.

And part of that, I think was because in the very early years they were dealing with a very small number of people that they could interview, right.

Yeah, they interviewed thirty five or thirty eight people, and when I left, it was up to fifteen hundred, So we had a much broader base or foundation to the information that we were basing our profiles on.

So basically, what.

We found was that there are a number of different ways that people become serial killers and a number of different ways that that manifests itself.

It's not one size of fis all.

You can't simply say, Okay, this is what motivates a serial killer. There's a spectrum of behavior. There's a tremendous amount of diversity among offenders, and that is evidenced in how they do what they do, why they do what they do, and how long they get away with it.

When we asked Jim Clemente to look into the Freeway Fantom case, he said, the best place to begin is to analyze everything we know about the killer.

We always start with picktimology, because looking at the victim and understanding everything about the victims is like holding up a mirror to the offender. There's a reason why he chooses these particular victims, and in this case, seeing the overwhelming similarities between these victims tells me that he had a very very strong preference and he offended mainly against children. They're petite girls too, and there's a reason for it. He didn't randomly pick these girls. He picked them specifically for that reason. Now, whether this was desire in him that was conscious or subconscious, I don't know whether he felt a certain way whenever he saw somebody he targeted as a victim, or whether he specifically laid out the plans. I'm going to wait for this kind of person to come into my sites, and then I'm going to wait.

For the opportunity to take that person.

I'm not sure about that, but the consistency with which he operated tells me this was an incredibly important thing to him.

So that's the first thing.

Second thing is I would absolutely categorize him as a preferential child sex offender. And what does that mean, Well, people throw around the term pedophile all the time, but what they don't understand is pedophilia is actually a diagnosis. You go to the DSM and you can look up the criterion to be diagnosed as a pedophile. But it's somebody who is sexually aroused by pre pubescent children. And this guy may be a pedophile, but the broader term is preferential child sex offender, meaning that he had a specific sexual preference.

And this can include the age, the.

Gender, the body type, the personality type, the circumstances, all of those things surrounding his victim choice. Because when he's hunting for victims, he's looking for vulnerability, accessibility, and desirability. And sometimes when the desirability factor isn't there, in other words, the person doesn't absolutely fit into that desirability factor.

He'll settle for whatever is available.

But in this case, because he picked patitue girls and most of them were young teens, that.

Was most likely his preference.

It's a criminal sexual preference and it's something that he has embraced in his life. In other words, many people have dark thoughts and desires, but this guy decided I'm.

Going to pursue them. I'm going to hide it.

I'm going to do everything I can to set up and be prepared for it. I'm going to fantasize about doing it over and over and over again, and eventually I'm going to actually be able to actually act on my desires. And that's what he did at least these six times, maybe more.

Clemente says. The next victimology factors to analyze are the different times and places where he actually abducted these girls.

He's clearly all over the map on that, but he's in a fairly small geographic location, and his body disposal sites are as well. And this tells me right away that this child preferential sex offender is from this area. He's not somebody who just passed through and doesn't really know the area. He's somebody who is actually invisible in this neighborhood. Nobody sees him as out of place. Everybody sees him as belonging, and so it doesn't raise the alarm that he's there. So he's able to operate with impunity in these neighborhoods. And that leads me to believe, if the demographics there are highly concentrated with minorities, that he is also a minority, and that means he could be African American, he could be mixed, but he's definitely seen as someone who is just part of the neighborhood, doesn't stick out like a sore thumb.

What about the location where he left the victims. Is it significant that he was leaving them by the side of the freeway.

It is significant, And freeways are interesting because millions of people use them, but very few people walk along the sides of them, right, so they're very accessible. But they're also not generally used for foot traffic, and so it's very easy to conceal someone just off of a very very busy highway because nobody usually walks along there. It means that he one has a car, two knows when he can get on and off that road without being detected. Most likely has a job or family situation which allows him to be out at any hour of the day or night. Because, believe me, choosing these victims and abducting these victims took a long time. He had to be out there a long time to get access.

To these particular victims.

They weren't doing things that they did every day at that time. That means he has to be available to wait for them to show up and to follow them, and then to be vulnerable. So they're not vulnerable while they're inside a store or with other people. They're vulnerable when they're alone. And in one case, for example, where he abducted a girl coming right outside of a corner grocery store, he had to be pretty bold because there were obviously other people around.

It said the.

Packages and things that she bought were right in front of the store, but that it doesn't say if it's on the sidewalk right outside the glass door, or on the street, you know, fifty feet away or around the corner.

I don't know what the.

Actual facts are, but he definitely took a risk with that one. And when you see someone take a great risk like that, that means the desirability factor is through the roof. This is exactly who he wanted, and he was willing to take a great risk to get her.

So this is important.

That tells me something in terms of how highly she might be ranked on his desirability factor.

Meaning that this is sort of his ideal.

Yes, it's closest to his ideal. The highest risk that he took is going to tell you what he wanted.

The most.

The next detail we looked at was the length of time that the killer kept each victim before dumping their bodies.

The first two were the ones that he kept the longest.

Yeah, Carol and Darlinia, right.

And so the first one, I would think it had the most planning involved. This is something he led up to for a very long period of time. He was fantasizing about doing this. Everything was in place, and he did what he did, and he planned to keep them probably for an extended period of time. But it never goes as well as they plan. Never, And so when he gets down to the third victim, it's eight hours later. The fourth victim, it's three hours later, the fifth victim it's six hours later, the seventh victim it's eight hours later. I think what he found was it's difficult to keep someone alive for a time and keep them hidden. He may have had some change in his circumstances, his relationship or his living circumstances, or wherever he kept these girls. But also he wasn't a killer until he killed his first victim. It may have taken him longer to form the intent to actually take their lives. And we see with Brenda Woodard that she received a tremendous amount of violence and anger from the offender, and she happened to be.

The only eighteen year old, the only adult.

She may have had more wits about her, She may have been stronger willed, and she must have fought more than the other. And I think because there was a ten month gap after that offense, she really affected him what she was able to do and maybe how close she was to being able to get away and.

Then ruin everything for him.

I think that really made him go underground for a period of time.

So what are we to make of the note that was found with Brenda Denise Woodard? This is tantamount to my insensitivity misspelled to people, especially women. I will admit the others when you catch me if you can freeway Phantom.

Well, there are a couple of things about it.

One is that he's obviously loving the moniker. This is why we tell media outlets do not nickname offenders.

We don't do it at the FBI, but we.

Do encourage the media to not name offenders, just like we tell them not to put a picture and the name a school shooter up after they've been caught or killed, because What it does is it gives other people who are like minded the idea that they can become famous too, Because many of these offenders don't have a good self image.

They're actually they feel.

Terrible about themselves and they're trying to feel more powerful. Particularly when you have this kind of offender who's attacking petite girls. This guy feels powerless and he wants to feel powerful. So this guy wanted to communicate because he wanted to sort of revel in the fact that he'd been given a moniker by the media. You won't hear me say it, because that is not something I encourage at all. Giving him a moniker only feeds his ego and can actually embolden him to kill more.

The next thing I'll say, and this is part of the profile.

Is that it's clear that he had a fairly correct use of the word tantamount.

I believe he used the word because he wanted to impress the readers.

He wanted to show off, and this is something that he will do in his real life all the time because of his.

Poor self image.

He feels the need to prove his greatness, and whether that's in his vocabulary that he uses or in the quote conquests that he makes. He wants to prove how much of a man he is, and this letter, especially when he has used these multi syllabic words to show off and he gets one of them wrong. So I think I should just launch into the profile.

Yeah, let's do it.

Next time.

On Freeway Phantom, I believe that he's likely short himself, although he has very powerful hands, probably due to the kind of work he does.

But I believe he's not scary. He's able to get close enough to these victims to not scare them away before he can control them.

One of the things that he said that really made sense to me is the fact that he believes that this person fantasized about this, especially with the first VIC, and planned it, and that's why he was able to keep her.

A lot of variables play in the closure rate. We live and die. Some people by the street code, some people out there. They know who murdered this person, they know who committed this armed robbery, but they won't come forward.

Freeway Fantom is a production of iHeart Radio, Tenderfoot TV and Black Bar MITZVAH. Our host is CELESE.

Hilly.

The show is written by Trevor Young, Jamie Albright, and Celess Hilly. Executive producers on behalf of Our Heart Radio include Matt Frederick and Alex Williams, with supervising producer Trevor Young. Executive producers on behalf of Tenderfoot TV include Donald Albright and Payne Lindsay, with producers Jamie Albright and Tracy Kaplan. Executive producers on behalf of Black Bar Mitzvah include myself, j Ellis and Aaron Bergman, with producer Sidney Fools. Lead researcher is Jamie Albright. Artwork by Mister Soul two one six, original music by Makeup and Vanity Set special thanks to a teammate, Uta Beck Media and Marketing and the Nord Group. Tenderfoot TV and iHeartMedia, as well as Black Bar Mitzvah have increased the reward for information leading to the arrest and conviction of the person or persons responsible for their freeway fan of murders. The previous reward of up to one hundred and fifty thousand dollars offered by the Metropolitan Police Department has been matched a new total reward of up to three hundred thousand dollars is now being offered. If you have any information relating to these unsolved crimes, contact the Metropolitan Police Department at area code two zero two seven two seven nine zero ninety nine. For more information, please visit freeway dashfanom dot com. For more podcasts from iHeartRadio and Tenderfoot TV, visit the iHeartRadio app, Apple podcast, or wherever you listen to your favorite shows. Thanks for listening.

Monster: Freeway Phantom

Monster: Freeway Phantom