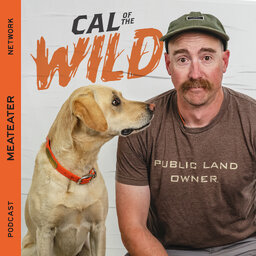

Ep. 383: Cows and Ocelots with the East Foundation

In this week's interview, Cal sits down with Jason Sawyer and James Powell of the East Foundation to learn more about how their cattle operations work to conserve wildlife and habitat in the deep South of Texas.

Connect with Cal and MeatEater

To learn more and get involved with any Cal to Action, click here.

MeatEater on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, Youtube, and Youtube Clips

Subscribe to The MeatEater Podcast Network on YouTube

From Meat Eaters World News headquarters in Bozeman, Montana. This is Col's Week in Review with Ryan col Cala. Here's Cal, Hello everybody, It's a rainy Tuesday here in bos Angelus, Montana. Another fantastic interview episode coming at you here on the Call of the Wild podcast feed. This week, we've got the East Foundation. If you got long memories, you may recall some previous conversations and mentions with the East Foundation, specifically around ocelot work. Today we will probably talk about oslots, which is not an African jungle animal. We have them here in the United States, just barely, and we're probably going to talk about an interesting new threat to wildlife and cattle. And really that's kind of the intersection of the East Foundation, which their tagline here is we promote the advancement of land stewardship through ranching, science and education. We say it all the time here on the Cow's Week in Review podcast. Tall grass makes fat cattle, and tall grass is also great for your pollinators, your big gnarley mule deer bucks or antelope bucks. Fire resistance, drought tolerance, keeping those nasty invasive species out is just a healthy landscape with me today is James Powell, director of Communications for East Foundation, as well as Jason Sawyer, who's the Chief Science Officer, which is a heck of a title. Jason and Jordan, I know we've been trying to pull this together for a while. Thank you so much for making the time, and can you tell us a little bit about who you are and what the East Foundation does?

Sure, yeah, we're sure glad to be with you today.

Again, it's been a minute since I think Neil visited with y'all a little while back. The East Foundation, as you mentioned, our mission is to promote the advancement of land stewardship.

But really what the East.

Foundation is is a private, working landowner that operates cattle ranching and maintains landscapes really for the benefit of both productive ranching operations as well as wildlife conservation.

Our operations are all in Deep South Texas.

We operate on about two hundred and seventeen thousand acres of private rangeland it's one hundred percent rangeland no cultivation, no you know, real improvements other than water developments and fences. And really our overall purpose is to maximize the long term value of these landscapes and enable better decision making by stewards of working lands, including ourselves.

And when you say working lands, I've been, you know, a guest invited to go check out some different conservation programs and projects on big properties in Texas. But I wouldn't necessarily call them working land. They're beautiful parks what might be more appropriate description. But when you say working lands, what do you mean?

Well, sure, you know, for US, working lands is as that would imply as are landscapes that produce. They do their jobs, they're put to work. They provide Now, they provide for wildlife habitat, which is an important value proposition in many ways, but they also provide for food production, they provide for open space, and really, I think the notion of working lands is that they are intentionally productive. We put them to work. Now, there's certainly a place for preserves and refuges, and you know, areas that we would say are not working lands, they've been taken out of production for some other purpose. And you know, I'm not not trying to cast any stones at that, but the majority of land in the United States is working land, and most of the wildlife habitat of the United states occurs on working lands, and.

So it's really that confluence.

You know, the conservation of these things is how do we achieve the wise use of these resources to maximize their long term value? And if they don't produce anything, then someone has to continuously invest external capital to sustain them, Whereas the goal maybe of a working landscape is that through its provisioning capability, it self generates the capital required to sustain its multiple use. That's probably not a dictionary definition, but certainly maybe my interpretation of what working lands are as opposed as you said, you know, a park or a refuge or a preserve.

Yeah, you're probably taking a crop of some sort off of working lands, be it crop of calves, crop of lambs, or.

Timber. Yeah, yeah, yes, sir.

Yeah, And and so that's really kind of the context of of what at least we mean when we say working lands that they produce a product, you know, and that production is necessarily aligned with the other amenities that that landscape provides, the other ecosystem services that people talk about quite a bit, and you know, that includes the course wildlife habitat, and it includes game species that are a direct value contributor to those landscapes. In many cases it includes non game species that provide other value and and you know, have amenity value as well as conservation, and I'm going to say, you know, ethical and aesthetic value, and all of those things need to come together and operate conjointly. And we feel like there's pretty good evidence that stewarded appropriately, that working landscapes actually can confer the best habitat and the best opportunities for those things to be sustained into the future.

So what's the rule that the East Foundation is focusing on? What's the history there?

Well, a little bit of history.

It kind of informs I guess our views of what we're here to do and why we're here. You know, the East family put this land together over a couple of generations, and they did that with livestock production. Now, they had a deep interest and passion for wildlife, and they personally enjoyed the wildlife on their properties, but they made the decision to keep these lands intact by placing them into a foundation that would outlive themselves right and outlive everybody else.

And so our charge.

Is to continue to ranch and that is part of our charge, and to do that in a way that benefits wildlife and the land resource itself and provides for scientific research and education to empower future generations of land stewards.

So that's a little bit about our.

History how we came into being, but it also informs very much our mission and how we intend to accomplish that. So we operate a working cattle operation. We're primarily a calcalf operator. We retain ownership on some of the calves that we produce as uterlines when forage conditions allow, and in that working ranch context, we also seek to secure the best habitat potential for the game species and non game species that inhabit our landscapes.

You know, South Texas is pretty.

Well known for abundant white tail deer populations for you know, important game birds like bob white quail. We have, you know, arguably the largest wild population of bob white quail left in the United States in the sandsheet of South Texas. We also are faced with some interesting newcomers relatively speaking to the landscape and Nilgai antelope, which are an incredibly interesting species that seem to have filled an ecological niche in South Texas. Their range doesn't extend much north of Corpus Christi Texas, so they stayed very far south, but they're native to India. They were introduced into South Texas about one hundred years ago, and that population has persisted and become unimportant resource in the region. We're also fortunate, depending on who you ask, they may disagree with our fortune, but to have some notable endangered species present on our landscapes, like ocelots that I know you've talked about before with Ease foundations. And an interesting thing to note there is that you know the presence of these endangered species, we view that as a responsibility, right they're there, that we hold those wildlife in the public trust. The public depends on us as lands too to sustain those populations. I mean, that's a responsibility that we have. But interestingly, cattle have been present on this landscape for about three or.

Four hundred years, and.

We would say that part of the reason that oslots still call that ranch home is because it has been a cattle ranch and it hasn't.

Been converted into other use, and.

That landscape still because of ranching, really has remained intact. And so we actually think that's a really positive example and maybe the misunderstood example of the importance of working lands and conservation.

Yeah, like Jason said that that ranch, the El Salis is right on the coast near Port Mansfield. If it wasn't a working cattle ranch as we're running it right now, that land would have been prime for development, could have easily been converted just outside of Port Mansfield into subdivisions and other highest best use you know in air quotes ways, and those oscelots that are there, some of the last that are in the state of Texas in the US, probably wouldn't be there anymore if it wasn't a cattle ranch.

Yeah. You know, I was just in d C the other week and it was chatting with a lot of members of the egg community that were in the same same room. And you know, I think right now there's a real heightened awareness between the hunting side of the world, the outdoors public land folks that we need to really get some common language with with the egg producers. Protecting those big family ranches is critical to long term wildlife and habitat and you know, among many other things, right like, we want to save ranching and wildlife, and in order to save wildlife, you got to save ranching too, right.

We would certainly agree with that that these things fit together hand and glove. You know, it's not one opposed to the other, or that they're held in tension. And the viability of these landscapes is equally dependent on wildlife value and livestock production value. In other words, if we remove one of those, the other is likely to fail. And so part of part of our objective, both as stewards and operators as well as as researchers and educators, is continuously evaluating and innovating how we best achieve those goals. What decisions should we make. What's the best decision to achieve these outcomes? And we don't always know, so we do experiments and try to figure it out. And you know, this notion of continuous improvement is also important there as we think about the future, whether it's of you know, ranching as a cultural activity or as a food producing activity, or hunting as a cultural activity or a food producing activity. Right, they share many common features and they share the same piece of ground, and so it's in all of our best interests to make sure that we make the wisest decisions about being able to do those things together. For a very long time, you know, for forever hopefully.

Well yeah, you know, the wildlife world, let's just say, on the on the public land side of the fence, maximizing returns for this season can have very detrimental effects on the next season and the season after that, especially taking in environmental factors. There's no difference on the private side of the fence. If you're a cattle producer and you overload the ranch trying to get the best return you can for this season, well that could set up the next season for failure or the next generation on that place for failure.

Absolutely. Yeah.

You know, we have research on like quail, right, Jason mentioned Bob White quail in Texas. A lot of our research and Jason can go more into this. You know, we're doing fifty plus projects right now, research projects at any given time, game species, non game grazing strategy, things like that, and there are a lot of that research is at the intersection of ranching and wildlife management. We talked you mentioned harvest there cal and one of our studies on Bob White quell is sustainable harvest of Bob White quell. You know, one of the prescriptions in South Texas has always been well, you can harvest twenty percent of the quail every year and that'll be sustainable in perpetuity. But no one really ever had set that up as a true experiment in South Texas to prove whether that was actually true or not. And so a lot of the some of the folks on Jason's team are testing things like that, like just how much harvest pressure can a bob white quail population handle in working ranch land South Texas landscape or not.

A good good friend of mine, old T Edward Nickens, Eddie Nickins, I know, has written an article or two on some of the quail stuff, And man, if you look at how much money goes in per bird in a lot of famous quail areas in the US, it's pretty amazing that it really boils down to a handful of things, right, like on that healthy habitat. Everything else is kind of marginal returns if you're not investing in that habitat and habitat management, that's right.

Well, and you know, that's been one of the really interesting evolutions. And maybe you know a role that we feel like is very important for us is you know, we feel a responsibility to do these things we feel responsible to understand more about better decision making for stewardship, but we also have to be relevant and so doing that in the context of a working cattle operation, and doing that at scale on Rangeland in South Texas is also really important. And so this our overarching COIL projects. One of the things that's unique perhaps about us doing those things is that we're deploying that at operational scale, So that controlled experiment where we can compare a twenty percent very strictly executed twenty percent harvest quota against non hunted areas with grazing, you know, interspersed into that, we're able to do that at you know, right now, we have about thirty five thousand acres in the hunted treatment and about the same out in the reference sites or the controls the unhunted areas, all.

Of which are subject to cattle operations.

And so at that scale, right we start to really understand the landscape level impacts on populations and make better decisions for individual landowners, you know, give them the ability to use information well as well as informed regional trends, and you know, and that's something that's difficult for many others to do within the constraints of their own systems, and so the scale of work is really important in the duration. You know, quail populations are a great example, right, that's a boom and bus cycle, I mean, and a few inches of rainfall at the right time of the year is a huge difference maker every year. And so for us be it able to evaluate these things over long periods of time. So we're about eight years in on this sustainable coil harvest project and to be able to execute that over long periods of time to really understand these long term impacts, as you mentioned, is also we think of a vital element of the work.

That we do and it's you know, in research that can be applied at least to some degree everywhere. But you're nimble enough with your operation to actually be able to implement this year over year and see what the results are, which is super cool.

And you know, one of the interesting things that comes out of work like that kind of the intention that we have and how we do that is as James mentioned that you know, this notion of the intersection of livestock production and habitat for wildlife is that you know, quail do better with some grazing pressure they like a mid serial stage rangeland you know, and they need room to navigate and room to operate. And they they are food sources. They want some diversity there. And we can actually promote the beneficial aspects of habitat for quail with properly applied grazing. And so the removal of grazing completely from our landscapes over time is likely detrimental to quail abundance, not positive for it. And so again a great example of how, you know, all things work together for good when we have to kind of keep our eye on the ball, you know, and don't forsake one for the pursuit of the other.

We talk about this all the time in various ways, right, But you know I'd carry the label of a hunter, right, Well, there's plenty of hunters out there that I don't want to be associated with. And ranching and farming. You can see that pretty plainly looking across to let's just say a bad neighbor's fence, right and you're like, well, things are going well over there, right, And why is that? So when you have a good model, especially when it's replicable, accessible, it can be really contagious, right In a.

Good way volunteer your point.

You know, we can all look around and we try really hard to kind of operate with the mindset of what I said, how do we enable better decision making? And first and foremost, we want to make better decisions. We want to do the best we can do, and we need better information in order to make better decisions. And that kind of fuels our science. You know, what questions should we ask? Well, the things that matter that make better help us make the best decision. And when we look, you know, we drive down the highway and you look over somebody else's fence, and it's pretty easy to ranch their country for them from your your windshield.

You know.

And or like I said, you you know that there might be folks that that hunt that maybe don't don't do it in a way that's as good as it ought to be for the betterment of the resource and maybe even for themselves. But you know, we try pretty hard to say, you know, it's not I would never I would never kick another man's dog, you know, And I would never presume to tell you what you ought to do. However, I think that when we do look across that other that other fence and think you know that they're having a tough time, that country is in tough shape, or it looks like a series of decisions that went wrong. What drove them to that? Why is it that way to? You know, you asked that question, why why is it that way? And can we then take that on and think about, Okay, somebody might have made a series or felt forced into a series of decisions that ended up being detrimental to the future of their operation. Is there a way that we could could generate information that would help them make a better decision next time? Can that ranch be healed, you know, by making a series of better decisions because they're better informed going forward. And you know, that's the amazing thing about most of these landscapes is that that you can start making some different decisions and change the future. Sure of that, Rangeland I mean it is within our capacity to do that, And that's pretty powerful.

I imagine there there's producers out there as well who are like, I want to run this many head of cattle on this much acreage? Can you help me do that?

You know that that does come up quite a bit.

And uh, and so we're also pretty honest about that.

You know, here's here's a way.

And we're continuously working on methods to better assess our own capacity. You know, so, what is the capacity of our of our land to support cattle populations, deer populations, et cetera. How do we better assess that so that we are more appropriately applying implementing population management and lifestock management on the landscape. And yes, people frequently find themselves in a situation where they say, well.

I've done the math.

I have two thousand acres of rangeland in a twenty inch rainfall zone, and I need to run three thousand cows.

On this in order to pay bills.

Well, that's not going to happen, you know, And so are there ways for them to rethink or reinvent the business where they're better able to match their utilization with the resources they have. And you know, and sometimes the honest truth is is that they have a mental model, right that they have to do a certain thing, and maybe what we need is to help them see that, you know, they could innovate and find a different approach that allowed them to operate more appropriately within the capacity of the ranch. That's a hard thing, you know, that's a really hard thing. But it's definitely something that comes up quite and you know, and we face that ourselves. I mean, we you know, there's a lot of incentive to increase inventory if you're a cattle operator, but we also recognize that there's an optimization point and finding that is the real challenge, that that's the goal. And so you know, again we face the same challenges and problems as others, so we at least understand some of those things that are driving decisions and how to be on guard, you know, and not let yourself get fooled into a decision that seems appropriate for today but maybe detrimental for tomorrow.

We were hiking a ranch in Sonora one time for Col's deer and a friend of mine. You know, it was similar to summer Texas, you know, real real brushy and everything sticks you And a friend of mine said, man, what would this place be like without cattle? And I said, I don't think we'd know, because I don't think we could hike through any of.

It, right, right, right.

And you know, it's like wildfire, you know, I mean, prescribed fire is good, wildfire is bad. And you know, all things can be overdone, but they can also be underdone. You know, the removal of fire or the removal of grazing altogether is often detrimental as well.

Oh yeah, and I think in this case, having that natural in quotes deforestation.

Was good.

It was the only thing that was up that landscape to any other sort of forbes.

Right, So right, how you create opportunity for the species that those that those deer depend.

On, you know, Yeah, because they don't live just in the brush, neither did the turkeys or the quail. They every part of their day for all those species, as they get out of that stuff into the grass for at least a little.

Bit, Yeah, go go find the goodies where they can find them, you know. So it's interesting that, you know, there's currently pretty big issue that I think many people have forgotten was a problem at one point in time, and that's New World screwworms, and and the people who do have some scarce memory of that pest perceive it as a livestock problem. You know that that was a problem in the you know, early nineties, well, late eighteen hundreds, early nineteen hundreds, before it's eradication in the nineteen sixties in the US, people you know, perceived that was a livestock operators problem and don't recognize that the enormous impact that that had on wildlife populations. You know, screwworms in Texas in the nineteen fifties, eighty plus percent of the fawn crop would be lost every year to screwworms. And you know, an adult deer succumbed to as well bucks, you know, during rut when they injure themselves, become susceptible and.

Perish from that.

And so you know, after screwworms were eradicated in Texas, the deer population doubled within the next five years and has quinn tippled since that time, went from you know about you know a million and a half maybe some some estimates under a million white tailed deer in Texas to almost six million today. And you know, is that all because the screwworm eradication. No, but certainly that was a significant depressant on those populations.

That's been relieved and and again.

People perceive it as a livestock problem, but kind of like, you know, the ranchers and the hunters are really all on the same side here.

Yeah, that parasite can infect any any warm blooded mammal.

I mean it.

You know what we talked about, Nilghai, We've talked about you know, there's there's a feral hog issue now, so you've got a bunch of feral hogs that could be vectors for those screw worms. They can even infect humans. So down in Central America, where it's always still been around, there are non human infection cases. And it doesn't always have to be a gaping open wound. At Jason's point, it might just be a tick bite that becomes infected by a screwworm and then within a matter of days you have a serious, even life threatening infection on your hands.

And you know where this.

Is something that's kind of, like Jason said, it's been forgotten, but all of a sudden, it's a big deal again. You're seeing it and then on Fox News and you're hearing the Secretary of Agriculture talk about it now all of a sudden, because it's like it's coming north again out of Central America into into Mexico. I know Jason and his science team are tracking this very carefully because, as he said, it's not only going to potentially affect us as producers, it could devastate wildlife populations and in South Texas or as far north as those will be able to move. Right, it's a big potential problem, not just for ranchers but also for hunters.

And so where where's East Foundation weighing in on this? You're you're monitoring, Jason, but are there some potential projects here?

Well, you know, we are trying really hard to be a voice and also trying to connect. You know, thankfully, USDA zag Research Service has never given up the fight on screw worms and they have an entomology unit a Llow here in Texas who works primarily on on these sorts of insect pests and tick pests, and they have sustained research over the last fifty years to continue to develop methods to you know, do surveillance and response and produce the sterile flies that are used to combat screwworms and eradicate eradicate that pest. So we've made sure to engage with them and see how we might be able to engage in research programs with them to increase surveillance capabilities and innovate technologies for surveillance of the pest, because you have to know it's there before you can do anything else about it. Certainly we want to be engaged with with other organizations and inform landowners and operators again, create that awareness that this is certainly a livestock problem, but not only a livestock problem. You know, you mentioned being on a property in Texas that maybe had dedicated themselves exclusively to wildlife management. Those folks are very vulnerable here and often again they don't perceive the threat because they associate it with livestock, and so our engagement here really is to understand the problem, enable better decision making by informing folks seeing beyond the obvious and recognizing the eminence of the threat and its importance in the United States to our food supplies but also to wildlife conservation. You know, we talked about the last remaining population of oslots you know in deep South Texas. Well, they get tick bites too. They are susceptible to this as well.

You know, it's not just a.

Livestock problem, and so so you know, I'll be honest with you, I hope and pray that we know have the opportunity to do direct research about treatment for screw.

Worms on our operations. Yeah, I hope they don't ever get here because they don't get here.

And the big thing that, you know, the thing that needs to be encouraged right now, is the redevelopment and restarting of sterile fly production production facilities. So the way that this was fought back was a couple of I mean it was genius, really, a couple of scientists came up with this idea where you breed sterile male screwworm flies. They then out compete the males in the wild to breed with the females in the wild. And so by the sterile males breeding with the females and not producing viable progeny over a lot of quick generations of reproduction, they wiped that they wiped themselves out by by being outbred by sterile mals that we were making in factories by the hundreds of millions. So it was a genius solution to the problem, maybe one of the best pest control things that's ever happened in human history. The problem is is that once we got rid of them in this part of the world and push them all the way back down into Central America to basically what people are I think referring to is the dairy and gap area right, that very very remote area in Panama. Now they quit producing the flies except in one place. So what needs to potentially happen now, and maybe fairly quickly, is that we get some of those product those sterile fly production facilities built and back online very quickly, so that we can deploy those quickly if they're needed, you know, if they get out of southern Mexico into ord the Mexico and start getting up to the our southern border and threatening you know, like like Jason has said, it's not just a cow problem, it's going to be a wildlife problem as well.

And a great example there, you know, is that you know, to James's point, like, hey, we want we we pushed it out, pushed it all the way out of the US, all the way south across Mexico, all the way down south of Panama.

We want.

And and you left you left one one place on guard duty. Yet you got one production facility in the world remaining that produces sterough flies and trying to keep that threat at bay. Well, some jumped over the wall, right, they overwhelmed the last remaining guard there, and so now that facility is perduction capacity might not be enough to keep up the fight.

So you got to have you got to have more.

And again, fortunately the ag Research Service with USDA has a strain that they've developed that if put into practice, could probably double the production of that one facility pretty rapidly. But even that might not be enough. And some additional production facilities further north, you know, in the US because now it's in Mexico. It's kind of jumped over the guard, right, and you got to push it back. So this is something obviously that's on our minds a lot right now, and we're trying to be the best partner we can be to other research agencies and to the the you know, USDA and state level and health agencies like ATHIS for USDA, or Texas Animal Health Commission in Texas Parks and Wildlife within Texas to be forward looking and think about how we manage this threat. And it's certainly not something that we can wait for, you know, we need to go to it, not not wait for it to come to us.

Yeah. Boy, it might be like an emergency funding situation here depending on what federal dollars get released. But as you're saying, hopefully the awareness is enough to prevent an emergency situation anyway.

Absolutely, And you know, again we're private landowners and we're not necessarily you know, I'm must speak for myself. I don't believe necessarily that the government needs to take care of everybody every single day. But there are roles, right, This is one of those roles when you have a threat that is larger than any one entity.

And when we.

Look at the historical effort here, it was a combination of private landowners and organizations, conservation groups, livestock organizations, and the federal government that came together to create the solution. And that's kind of where we see ourselves today is you know, this is an effort, this is what this is what government is for, is to safeguard the resources and productivity of the nation. And this is that sort of an issue.

And like you said, it's not just a producer's issue. The wildlife effects are us You're talking about on a normal year having eighty fond mortality. Is that's impactful.

And and you know how rapidly that decimates the population right to an unhuntable, unsustainable level. And you know it affects people in town too. You know, the effects on productivity and their recreational opportunities and the price of food. You know, all of these things are affected. And you know, I'm the last person to ever want to, like, you know, be a fearmonger or anything like that.

But reality is reality.

And helping people understand the importance of this kind of an issue when it might seem far away from them, you know, is we think important and something we're certainly you know, spending a lot of our our thought energy on right now.

For sure?

Are you telling me that hunters aren't the only ones who only get off their butts when the threats in their backyard.

I think that's a human condition, you know, closest alligator to the boat, and and sometimes it's helpful to have you know, I've got my youngest son is really good. If you stand him up a little bit higher on the boat, he can see a little further out, and he's got better eyes than me, and he can sometimes see something from further away than I can. And it's useful to have a lookout, you know, and turn right. We all have to tend with to you know, contend with today's problem. But but we need to keep our eye on the one that could be a way bigger problem tomorrow.

Yep, that's the truth. Well, I'd love to have you back on and dig into this es a topic as it evolves here in the US.

Another interesting development, right.

Sup, Super interesting and it's just just too big to fit in this episode. But if folks want to get a hold of the East Foundation and you know, learn more about this crossroads of ranching wildlife habitat, sustainable long term use and yields also screwworm or you know, having a working landscape that involves endangered species such as the ocelot, or maybe it would be lesser prairie chicken ranching country or greater sage grouse ranching country, or or right forridging pigmyls, blackfoot ferrets. That damn list? How did? How do folks get a hold of you?

So we have a We just just put out a brand new website at www dot Eastfoundation dot net. So that website is months old and specifically designed to be a great repository and online library of information about all the things we do, all the research we do with all of our university and agency partners. You can find out about what we're doing for the oslot issue, what we're studying in terms of game species like nilghai quail, whitetail deer, and what we're doing in terms of ranching research and operation, you know, adaptive management and ranching as well. So our website East Foundation dot nets probably the best place to go. We also have a Facebook and Instagram. Just look up just type in east Foundation and you'll you'll find us there. You've been putting out information on this screw worm issue on social media with links and direction to other resources so people can get up to speed on this really quickly by following us there.

Excellent, excellent. Well, if folks have additional questions, Chief Science Officer Jason Sawyer, please right into ask c A l ask Cal at the meeteater dot com. Will either get these folks back on which I think we should, or I'll get your questions to them and we'll answer them on the show.

Well, we would look forward to the opportunity to visit with you more about any of these or other topics. We just really appreciate all y'all do and the great awareness that you'll bring to Honting in the intersection of these issues and how important they are, you know for everyday people. I mean being relevant matter, and and we just really value everything that you do at Meat Eater and appreciate the opportunity to visit with you today and would love to have a chance to do it again.

Oh darn right, we'll make it happen. You guys, keep keep working on keeping the working lands in working fashion, not turning into condos, and we'll we'll be buddies for sure. So thank you so much, and we'll talk to you.

Soon, Yes, sir, take care, Thank you. Thanks,

Cal of the Wild

Cal of the Wild